Back የባግዳድ ውድቀት (1258) Amharic سقوط بغداد (1258) Arabic سقوط بغداد (1258) ARZ Bağdadın mühasirəsi (1258) Azerbaijani بغداد موحاصیرهسی (۱۲۵۸) AZB Обсада на Багдад (1258) Bulgarian বাগদাদ অবরোধ (১২৫৮) Bengali/Bangla Emgann Baghdad (1258) Breton Pustošenje Bagdada (1258) BS Setge de Bagdad (1258) Catalan

| Siege of Baghdad (1258) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Mongol invasions and conquests | |||||||||

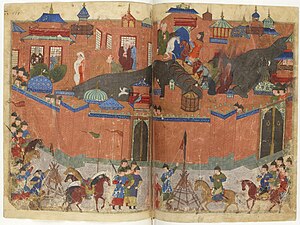

Depiction of Hulegu's army besieging the city, c. 1430 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Al-Musta'sim | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 138,000–300,000[a] | 50,000 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

200,000 killed (according to Hulegu) 800,000–2,000,000 killed (Muslim sources) | |||||||||

The siege of Baghdad took place in early 1258 at Baghdad, the historic capital of the Abbasid Caliphate. After a series of provocations from the city's ruler, Caliph al-Musta'sim, a large army under the Mongol prince Hulegu attacked the city. Within a few weeks, the city fell and was sacked by the Mongol army—al-Musta'sim was killed alongside hundreds of thousands of his subjects. The city's fall has traditionally been seen as marking the end of the Islamic Golden Age; in reality, its repercussions are uncertain.

After the accession of his brother Möngke Khan to the Mongol throne in 1251, Hulegu, a grandson of Genghis Khan, was dispatched westwards to Persia to secure the region. His massive army of over 138,000 men took years to reach the region but then quickly attacked and overpowered the Nizari Ismaili Assassins in 1256. The Mongols had expected al-Musta'sim to provide reinforcements for their army—the caliph's failure to do so, combined with his arrogance in negotiations, convinced Hulegu to overthrow him in late 1257. Invading Mesopotamia from all sides, the Mongol army soon approached Baghdad, routing a sortie on 17 January 1258 by flooding their camp. They then invested Baghdad, which was left with around 30,000 troops.

The assault began at the end of January. Mongol siege engines breached Baghdad's fortifications within a couple of days, and Hulegu's highly-trained troops controlled the eastern wall by 4 February. The increasingly desperate al-Musta'sim frantically tried to negotiate, but Hulegu was intent on total victory, even killing soldiers who attempted to surrender. The caliph eventually surrendered the city on 10 February, and the Mongols began looting three days later. The number of people who died is unknown, as the number was likely increased by subsequent epidemics; Hulegu later estimated the total at around 200,000. After calling an amnesty for the pillaging on 20 February, Hulegu executed the caliph. In contrast to the exaggerations of later Muslim historians, Baghdad prospered under Hulegu's Ilkhanate, although it did decline in comparison to the new capital, Tabriz.

- ^ a b c d Bai︠a︡rsaĭkhan 2011, p. 129 "In November 1257, Hűlegű set off from Hamadān in the direction of Baghdad. (...) With him were the forces of the Armenian Prince Zak‘arē, the son of Shahnshah Zak‘arian and Prince Pŕosh Khaghbakian. The Mongols placed considerable trust in these Armenian lords, whose assistance they had received since the 1230s."

- ^ a b Pubblici, L. (2023). ‘Georgia and the Caucasus’, in M. Biran and H. Kim (eds.) The Cambridge History of the Mongol Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. pp. 719–720.

The Georgian and Armenian aristocracy now was bound tightly to the Mongol leading class and the military became of primary importance. The Mongols forced their subjects to participate in their military campaigns. For the local aristocracy, it was sometimes necessary to contribute in order to get some immediate advantages from them. Therefore the intervention of Armenian and Georgian forces in Mongol military operations was not an isolated incident. (...) Around mid-1200, the whole Caucasian region was gripped by Mongol power on one side and the Muslim independent states on the other; the Ismā'īlĭs (Assassins) in the territory between Syria and northern Iran, and the Caliphate of Baghdad. When Hülegü began the military campaign against the caliphate, the Armenian and Georgian aristocracy took the opportunity to eliminate the menace and joined the Mongol armies. The attack on the Assassins' stronghold in Alamūt – which ended with the fall of the city in November 1256 – was planned and executed with the aid of David Lasha. Prince Zak'are, son of Shahanshah, participated in the operations against Baghdad in 1258 and the Armenian aristocracy was fully involved as well. Eastern Christianity embraced the conquest of Baghdad by Hülegü's army as divine revenge. The Mongols massacred the Muslim population of the city but spared the Christians. Hülegü gave the palace of the Dawādār (vice chancellor) to the Nestorian patriarch Makhika. Kirakos describes the fall of Baghdad in joyful terms and states that all the oriental Christians were exulting because after 647 years the "Muslim tyranny" had finally ended.

- ^ a b Biran, Michal (25 July 2022). Scheiner, Jens; Toral-Niehoff, Isabel (eds.). Baghdād: From Its Beginnings to the 14th Century. Leiden: Brill. pp. 285-315. doi:10.1163/9789004513372_012.

At the very beginning of 1258 Hülegü and his multi-ethnic armies—including Chinese siege breakers, Armenian and Georgian auxiliaries and quite a few Sunnī Muslim troops from Central Asia, Iran and Iraq— converged on Baghdād from all sides. Fighting began in earnest in mid-January, and the city was taken on February 10, 1258, when the caliph left the city and surrendered to Hülegü.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search